Dublin Gothic at Abbey Theatre, Dublin Review

Written by Ciarán for Theatre & Tonic

Disclaimer: Gifted tickets in exchange for an honest review

In December 2021, Ireland’s National Theatre, the Abbey, produced Thornton Wilder’s The Long Christmas Dinner as its seasonal offering. The production had to be aborted due to a surge in COVID-19 cases among the cast and public, but still, the play must have lingered in the minds of the Abbey’s decision-makers, as four years later this year’s Christmas production uses the same basic conceit; that is, the story of multiple generations in one location, with time progressing rapidly and without much warning, and characters ageing decades in minutes.

This is not to negatively contrast Barbara Bergin’s Dublin Gothic to its august predecessor, or even to damn it with faint praise – while The Long Christmas Dinner, like Wilder’s more celebrated Our Town, stresses the importance of small, personal stories, Dublin Gothic is a more wide-ranging, sprawling work that addresses broad cultural themes from mid-19th to late-20th century Ireland. This is reflected in its run time; at three and a half hours with two intervals, you need to be able to keep an audience’s attention. While the breadth of issues and characters means the production is baggy in places, there is a lot to love here, in a work that is nakedly ambitious, gorgeously performed, beautifully constructed, and consistently retains the ability to move its audience.

The place in question is O’Rehilly Parade (fictional) in Dublin’s north inner city, at the time of the play’s beginning, home to some of the worst slums in Europe (non-fictional). The characterisation of the tenement’s inhabitants is admittedly flat at first – they are two-dimensional cyphers you would expect to find in any interpretation of slum-dwellers of 150 years ago; the dashing revolutionary, the tart with a heart, the dreaming writer. Allied with the consistent rarity of hearing genuine working class accents on the stage, these early moments do not augur well, but when it settles into the rhythms of plot, character development, and mapping private lives onto public events, it clips along at a lovely pace.

With a cast of 19, all of whom play multiple roles, it is difficult to land on a key performer, but Sarah Morris is the centre of the work, playing the first act’s sex worker, Honour Gately, and her descendant, Nell Considine, at the play’s close. The initiating drama is the execution of Honour’s mother, followed by her fathering the child of a sleazy James Joyce replica, and then her ascension to comfort by acting as her landlord’s rent collector. She is complex, vulnerable, and shrewd; never a victim, but regularly victimised. Her counterpart is Ned Cummins (Barry John Kinsella), the revolutionary who leads a rent strike, the failure of which eventually leads to his alcoholism. The play then moves through the succeeding generations, as we see how their offspring interact with each other and the wider world, and the rapidly changing nature of Irish life, up until the 1980s.

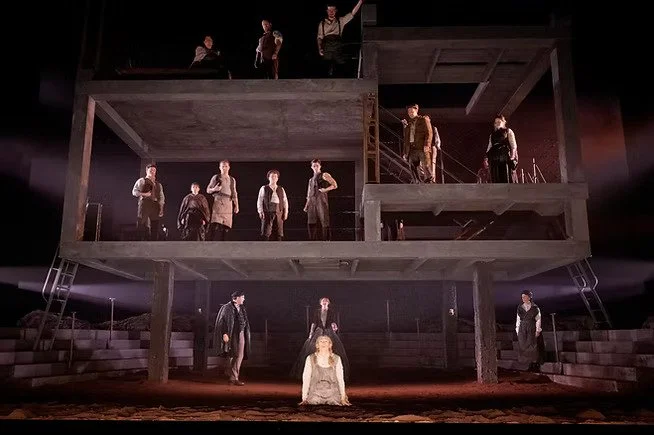

With so many different spaces, characters, and eras, the stage needed to be flexible and attractive, adaptable but effective, and in this, Jamie Vartan has excelled. The low, deep floor has a ring of tiered seating around it, and a structure with 4 levels that create that multistorey feeling of an old Georgian townhouse, regardless of what year is required. While it is a talky piece – characters speak stage directions as if they are reading from a novel, it is also kinetic, if even frantic at times, in a way that means boredom is not an option; there is always an intense human moment or movement happening, and for this choreographer Meadhbh Lyons deserves credit. Helming it all is director Caroline Byrne, who keeps this huge story under control; she is more than a match for the script’s ambition, and has evidently, and justifiably, been given a considerable budget. It is impossible to list all of the good performances, but special mention must be given to Thommas Kane Byrne – he plays Honour’s spoiled son, and then the romantic, fame-seeking, yet tragic Tiarnan in the final act. He has been a fixture on stage and screen, as a writer and performer, for a number of years, but it is still thrilling to see someone who is so blatantly destined to become a superstar this early in their career.

This is the Dublin of Sean O’Casey’s most famous works; the lives of the working class who bear the brunt of starvation, filth, war, sexual exploitation, religious control, and social exclusion. Following in O’Casey’s footsteps, Bergin delicately but clearly shows how her characters are impacted by the goings on in Dublin and beyond. Alongside her thinly veiled portrait of Joyce, there are also clones of Brendan Behan and revolutionary leader and schoolteacher Patrick Pearse. More than acting as an opportunity to allow people who get the gag to enjoy their cleverness, though, these characters show the dark underside of so many of history’s revered men – Behan was a brilliantly entertaining man, but also an unpleasant one; Pearse instigated the conflict that eventually led to Irish independence, but had radical ideas about blood sacrifice and martyrdom. This tendency becomes playful in the final scene – Bono is rendered “Bong”, and dies of a drug overdose – but Bergin also yanks us back into seriousness as her characters are confronted with the heroin and AIDS epidemics. As if to acknowledge or even apologise to Joyce, the final lines echo those of his short story “The Dead”.

Barbara Bergin’s language is crisp and witty, she has a tremendous ear for dialogue (typically – there are moments when it becomes too hokey), an evident love of her subject, and wonderfully daring sense of theatrical possibilities. Some of the themes here could have been more developed, for instance the eternal presence of our (individual and collective) past, which she uses ghosts to embody, but in a way that needed more elaboration. These are but minor quibbles, though, as Dublin Gothic is a welcome addition to Dublin’s literary history, and it is a deeply positive sign that the Abbey is mounting a piece with such daring and aspiration, and seeking to live up to, rather than constrain, its author.

Plays at the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, until 31 January

★ ★ ★ ★