Behind the Scenes of Shakespeare’s Globe in London

Written by Wendy for Theatre and Tonic

Shakespeare’s Globe is undoubtedly one of the most influential theatres in the UK, and recently, I had the fortune of being invited there. Not only did I get a glimpse of the technical rehearsal for the brand-new production of the musical Pinocchio, but I also gained a much deeper understanding of the Globe itself.

After a warm cup of coffee and some cheerful conversation, the tour officially began. To my surprise, this seemingly historic building is only 28 years old. It was proposed by the American director and actor Sam Wanamaker, and is a faithful reconstruction of the original Globe Theatre. The first Globe burned to the ground after Shakespeare, hoping to add a touch of realism to the play’s war scenes, and allowed a cannon to be fired onstage. Fortunately, no one was killed; some audience members even found the mishap rather amusing, though Shakespeare himself was far from pleased. A year later, the theatre was rebuilt by the actors, but it was demolished in 1644. The current building is therefore the third Globe Theatre. It was constructed using more than a thousand oak trees, with a thatched roof that had been specially permitted - thatch had been banned after the Great Fire of London in 1666. In just 28 years, the oak beams have already developed countless cracks. However, according to our tour guide, aged oak is far stronger now than it was when the theatre was first erected.

Back in Shakespeare’s day, the Globe could hold up to around 3,000 people. Today, the number is limited to about 1,500 at most. But personally, I definitely prefer watching a performance without being packed too tightly together. And compared with the old practice of having to pay another penny to re-enter the standing area every time you stepped outside, I much prefer the modern system of having a physical ticket.

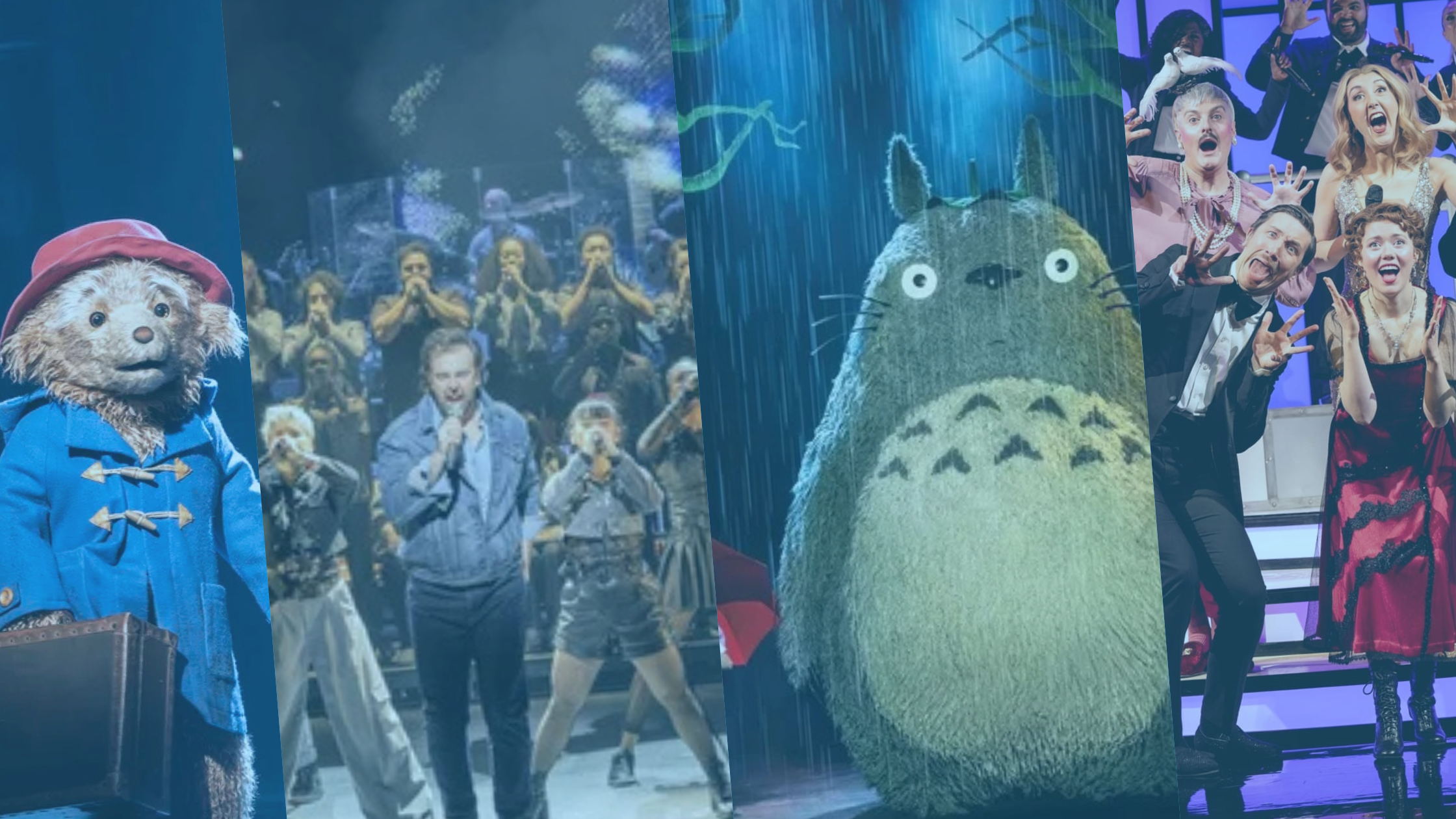

Just about halfway through the tour, a rehearsal began on the stage. In the cold weather, the actors all wore identical padded jackets underneath their beautifully crafted, fantastical costumes. Even so, they performed with the energy and focus of people standing before a full audience. At first glance from afar, the Pinocchio puppet didn’t seem especially elaborate in design, but under the coordinated manipulation of three performers, it came to life. Moreover, I was told that this production even has a designer dedicated solely to creating costumes for the Pinocchio puppet.

The tour didn’t end there. We were taken to different seats around the theatre to experience what it’s like to watch a play from various places. Some seats offered an excellent view, but if you happened to sit in the worst spot, you would see almost nothing but the actors’ backs. You wouldn’t be able to see the moon hanging above the stage or the set piece shaped like an open book, and a large pillar would block a lot of your view. As I listened to the guide’s explanation, I finally understood why Shakespeare often had characters verbally describe what they were doing in his plays - this was so that audience members who couldn’t clearly see the stage, as well as the actors, could still follow the progress of the story. In this context, lines that might otherwise seem redundant suddenly made perfect sense.

What’s even harder to imagine is that because Shakespeare’s company often had to perform several different plays within a single week, actors might receive their scripts only right before going on stage. Not only did they have no time to rehearse, but the script they were given might contain only their own lines. In other words, until they actually finished performing the play, the actors themselves wouldn’t know what kind of ending Shakespeare had written for their characters. Under these circumstances, they also had to rely on many props prepared at the last minute. When an actor heard another character mention a needed item in the dialogue, it gave them just enough time to react and bring that prop onto the stage. It’s said that in recent years, the Globe even experimented with a one-off production under the same conditions as in Shakespeare’s time, giving each actor only their own lines to recreate the experience as authentically as possible. This added a unique kind of charm to the performance.

After following our tour guide around the theatre, I realized that not only was it rewarding to see how a production takes shape, but the history of the theatre itself was far more fascinating than I had imagined. In the days to come, I hope not only to see Pinocchio but also to experience more of the Globe’s productions. I might even try learning a bit more about history, who knows?

For further information on Shakespeare’s Globe, including upcoming productions, visit the website here.