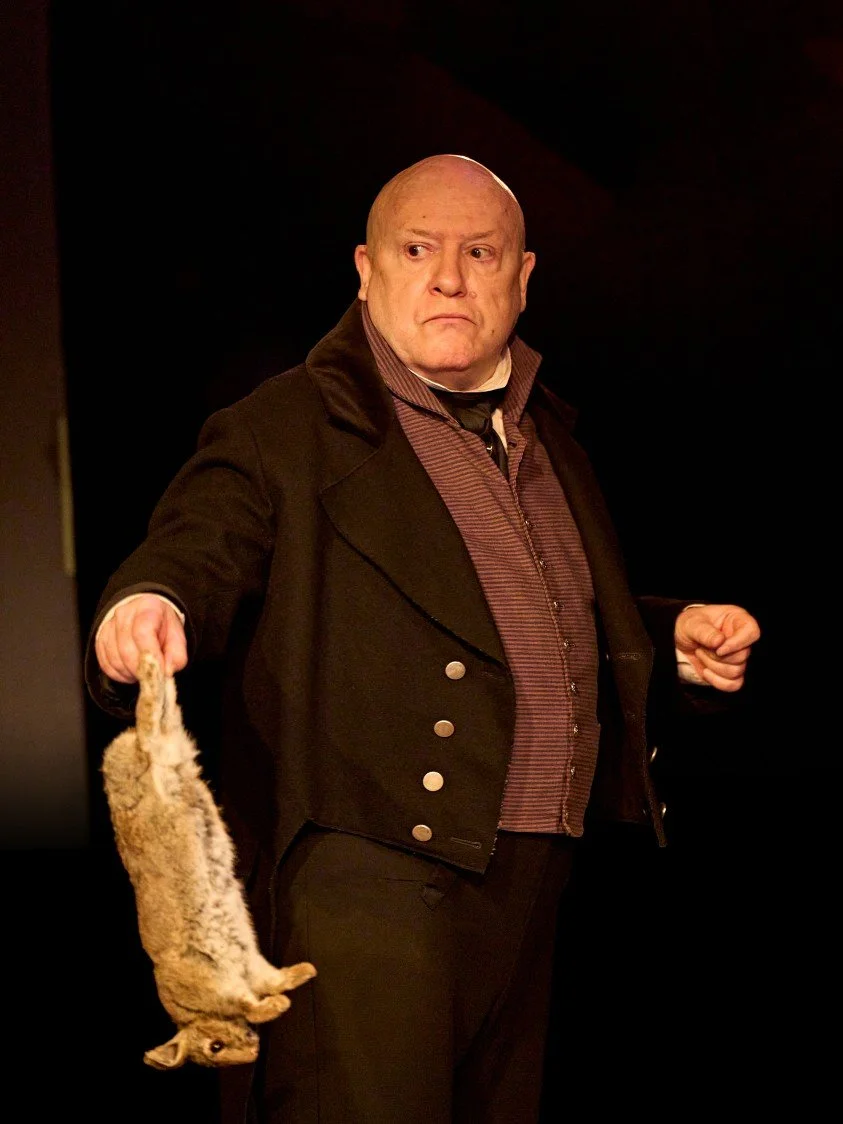

Arcadia at The Old Vic Review

Arcadia at The Old Vic production image. Photo by Manuel Harlan

Written by Ziwen for Theatre & Tonic

Disclaimer: Gifted tickets in exchange for an honest review

If one were to watch only a single play by Tom Stoppard, Arcadia would be the best choice. Many critics have expressed this view. The play was first staged in 1993 and won the Olivier Award for Best New Play in 1994. After multiple revivals, it has now returned to the stage of the Old Vic under the direction of Carrie Cracknell. In less than three hours, this theatrical space is filled to the brim with love, time, science, chaos theory, and literary history.

Originally, Arcadia referred to a mountainous region in the central Peloponnese of ancient Greece. Its terrain was remote, and life there centered on shepherding and a natural way of living. Later, after the Roman poet Virgil wrote his Eclogues with Arcadia as their setting, Arcadia came to carry the meaning of a pastoral utopia. Then there appeared the well-known phrase “et in Arcadia ego,” which means “even in the most ideal and innocent place, death still exists.”

This is also one of the meanings expressed by the play. The story unfolds in an interwoven manner across two different periods of time, both set in the same country house. In the nineteenth century, a thirteen-year-old prodigy, Thomasina (Isis Hainsworth), under the guidance of her tutor Septimus (Seamus Dillane), begins to engage in intellectual inquiry, while, amid academic discussions, love gradually starts to take shape. In the distant future, modern scholars (Leila Farzad, Prasanna Puwanarajah, and Angus Cooper) obtain letters, manuscripts, and mathematical notebooks from the past and attempt to reconstruct what truly happened. However, their seemingly well-reasoned conclusions turn out to be far removed from the truth.

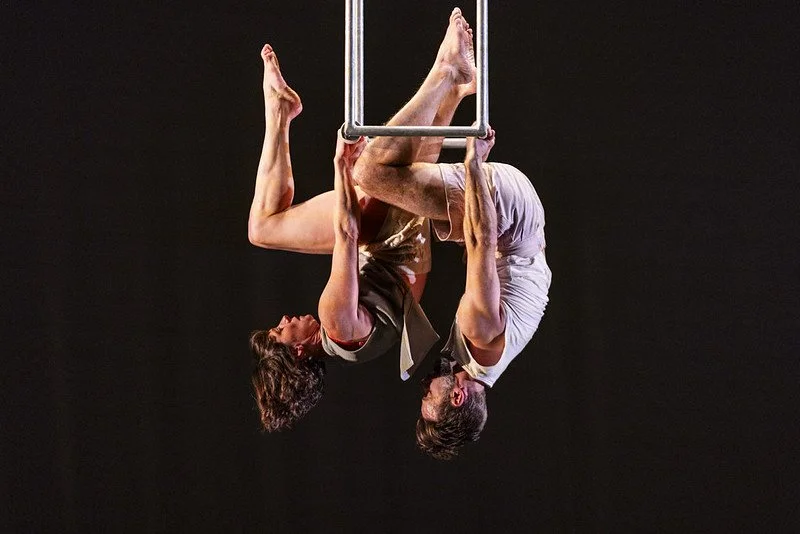

Alex Eales’s circular revolving stage design is extremely ingenious. Two strips of lighting suspended above the stage seem to outline two elliptical galaxies, while beneath them hang individual warm-glowing spheres that resemble atoms. At the center of the stage is a round wooden table with two chairs, and four benches are placed around the edges of the stage. The audience is seated around the stage, as if they too are situated within this room of scholarly discussion. In one scene, as the stage slowly rotates, books and notebooks are passed to people from the modern era from those of the past, and I felt as though I were witnessing the flow of time.

A play with such high-intensity dialogue places great demands on the actors’ abilities. Hainsworth’s Thomasina possesses an overwhelmingly strong sense of girlhood. Intelligent, innocent, and charming—these words immediately come to mind upon seeing her, and even when the timeline shifts to the modern era, one cannot help wanting to keep watching this energetic girl to see what she might do next. Dillane’s Septimus displays a kind of intelligence that is slightly sly; his speech is always tinged with irony, yet also carries a degree of tolerance and a hint of melancholy. Fiona Button’s Lady Croom is forceful yet with a distinct sense of humor. Farzad’s Hannah is serious, calm, and cautious. And Puwanarajah’s Bernard is ambitious, obsessive, arrogant, and romantic to a somewhat dangerous degree. However, because the modern characters spend much of their time discussing the truth of this nineteenth-century house, their individual characteristics feel somewhat one-dimensional. I find myself more curious about their personal lives beyond their identities as scholars. Perhaps they should not only be discussing people of the past; they themselves ought to be experiencing something that the audience cares deeply about.

In fact, compared with the academic discussions, I prefer the small personal details of the characters. Near the end of the play, people from different eras remain in the same space. Although they cannot see one another, Hannah and Thomasina simultaneously touch the petals of the potted plant on the table. And when the two pairs from different eras dance at the same time—one gentle, the other passionate—the image is filled with poetry. Especially when one knows that a radiant life like Thomasina’s is about to end, the beauty of the vitality she possesses in that very moment becomes all the more moving.

From the language of the play, one can very easily sense the author’s intelligence. Its literary quality can be said to outweigh its narrative quality far. Yet precisely because of this, I feel that I still do not know these characters well enough in their more human dimension. Arcadia today may require an audience that enjoys literature, philosophy, and science. Only with such a strong foundation of knowledge can one fully perceive its brilliance. However, even if that is not the case, it is still possible to savor a measure of poetry.

Arcadia plays at the Old Vic until 21st March.

★★★★